Key Points:

- William Stanley Jevons was a British economist credited with being the first theorist to make economics a mathematical discipline.

- In 1860, he developed the Theory of Utility, which states that a commodity’s degree of utility is a continuous mathematical function of the quantity available.

- Jevons invented the Logic Piano, which aids in calculating syllogisms: logical alphabet, logical slate, logical stamp, and logical abacus.

Who Was William Stanley Jevons?

Born on September 1, 1835, William Stanley Jevons was a writer, English economist, and logician. He was a major figure, both in Britain and internationally, in political economy and social reform. Jevons is most often credited with being the first theorist to make economics a mathematical discipline. He is regarded as one of the founders of the form of neo-classical economics, which dominates our current economic thinking and political discourse.

Early Life

Born in Liverpool, England, Jevons was born to the family of Thomas Jevons and Mary Anne Jevons. His father was an iron merchant and writer who also wrote about economic and legal subjects, while his mother was the daughter of famous England’s first abolitionist, William Roscoe.

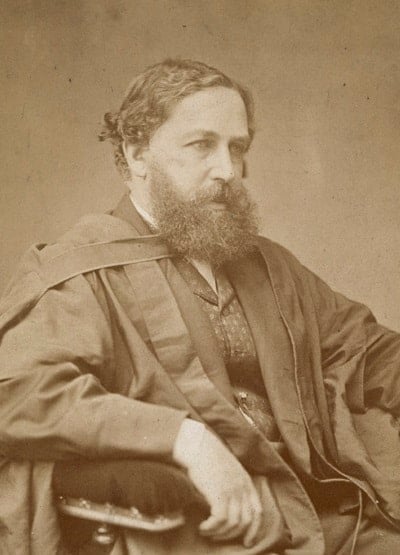

William Stanley Jevons

©Public domain, from Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository – Original / License

Jevons was sent to London at age 15 to attend the University College School, studying chemistry and botany. However, he was forced to leave school in 1847 due to his father’s business bankruptcy. Jevons began working as an assayer at the Mint in Sydney, Australia.

He worked there for 5 years before returning to the University College, London, earning his B.A. and M.A degrees.

Career

Phase 1

After dropping out of the University College, London, William Stanley Jevons got his first employment offer as an assayer at a new Mint in Sydney, Australia. Jevons wasn’t pleased with the idea of leaving the U.K.; however, he had to as his father’s firm had gone bankrupt.

While in Australia, Jevons lived with his colleague and his wife at Church Hill before the trio moved to Annangrove at Petersham, then Double Bay. Jevons spent 5 years working for the mint company before returning to the U.K.

Phase 2

After returning to the U.K. to continue his education, William Jevons earned his B.A and M.A degree from the University of London. Not long after, he was employed as a tutor at Owens College Manchester, now called the Victoria University of Manchester.

Phase 3

William Stanley Jevons was elected as Cobden professor of political economy and a professor of Logic, mental, and moral philosophy at Owens College.

What Was William Stanley Jevons Known For?

Invention 1 – Theory of Utility

William Stanley Jevon was known for was his Theory of Utility. Written in 1860, Jevon’s theory of utility became a major part of his general political economy theory and general logical principles.

The theory of utility states that a commodity’s degree of utility is a continuous mathematical function of the quantity available. It also cuts across the implied doctrine that economics is a mathematical science.

Invention 2 – The Logic Piano

In 1866, William Jevons designed the logical machine for making logic inference, called Logic Piano. The Logic Piano was usually regarded as the best-known logic machine of the nineteenth century.

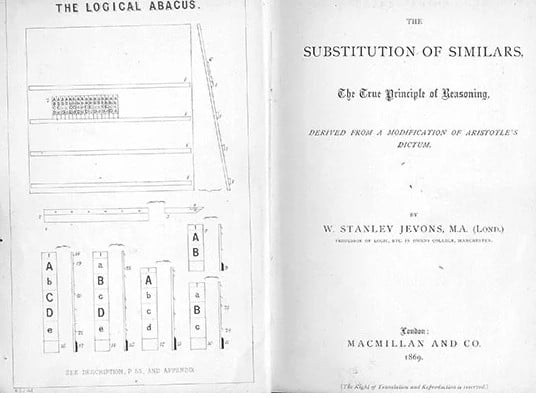

Jevons’ design that led to the manufacture of the Logic Piano was inspired by Stanhope’s Demonstrator. The device’s construction was announced in his 1869 logic textbook, Substitution of Similars.

It was the culmination of a long series of inventions and aids to calculating syllogisms: logical alphabet, logical slate, logical stamp, and logical abacus-all tools to write the lines of a truth table in a logical argument quickly.

Although Jevons’ interest in Logic began in the early 1860s while working as an assayer in Australia, his serious involvement and subsequent passion for Logic came about when, on his return to England, he met up with his former undergraduate teacher of mathematics, the famous logician Augustus de Morgan. It seems Jevons was one of the first in Britain to catch on to the importance of the newly developed formal logical systems of Boole and De Morgan.

Jevons read the Mathematical Analysis of Logic and An Investigation of the Laws of Thought of Boole and was fascinated. But he also saw problems with it, and by 1861 he was developing his own system of Logic based on what he eventually called the Substitution of Similars, whereby philosophy would be shown to consist solely in pointing out the likeness in things.

In 1863 he published his first work on Pure Logic, which was hardly a success, with four copies sold in 6 months. But Jevons was a great one for persistence.

In his 1869 logic textbook, The Substitution of Similars, he describes the Logical Abacus: a series of wooden boards with various combinations of true and false terms. They were intended to be arranged on a rack, and a ruler was used to remove certain excluded combinations. This was the basic outline of the device that, with the addition of levers and pulleys, Jevons had a Salford clock maker construct for him in 1869. Fitted within a wooden case and with a keyboard mounted on the front to operate the substitution mechanism, this was his Logic Piano.

The logic piano was a wooden box approximately 90 cm high. A faceplate above the keyboard displayed the entries of the truth table. Like a piano, the keyboard had black-and-white keys, but they were used to enter premises. As the keys were struck, rods would mechanically remove from the face of the piano the truth-table entries inconsistent with the premises entered on the keys.

The Logic Piano

©Public domain, from Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository – Original / License

The Logic Piano – otherwise called the biggest logic machine in the 19th century – can deal with up to four terms. Jevons had, in fact, wanted to build a machine capable of dealing with up to 16 terms, but it would have been too large and taken up a whole wall in his office. The logic expressions are typed (or perhaps played) via the keys of the keyboard, and hitting full stop removes all impossible combinations from the screen. The copula is the equals key, while the finis key resets the machine.

As Jevons’ adversary John Venn noted, this logic machine has no practical purpose, for there are no circumstances in which difficult syllogisms arise or in which syllogisms must be resolved repeatedly enough to justify mechanization of the process. Jevons countered that it was convenient to his personal work and valuable in his logic classes.

Invention 3 – Jevons’s Number

In his book, Principles of Science, released in 1874, William Stanley Jevons wrote: “Can the reader say what two numbers multiplied together will produce the number 8,616,460,799? I think it unlikely that anyone but myself will ever know.” This number, 8,616,460,799, soon became popular as Jevon’s number.

Charles J. Busk first factored the number in 1889, followed by Derrick Norman Lehmer in 1903, before it was factored on a pocket calculator by Solomon W. Golomb. Jevons’ number comprises 2 prime numbers, 96,079 and 89,681.

William Stanley Jevons: Marriage, Divorce, Children, and Personal Life

Marriage

William Stanley Jevons married Harriet Ann Taylor, the daughter of the founder and proprietor of the Manchester Guardian, John Edward Taylor, in 1867.

Children

Willian Stanley Jevons and Harriet Ann Taylor gave birth to Herbert Stanley Jevons in 1875, eight years after their marriage.

Tragedy

On August 13, 1882, William Jevons died after suffering from ill health and sleeplessness. Jevons drowned to death near Hastings while bathing and was buried in the Hampstead Cemetery.

William Jevons Published Works and Books

Book 1

William Jevons published his logic textbook, The Substitution of Similars, in 1869. In this book, he described the Logical Abacus as a series of wooden boards containing various combinations of true and false terms.

Book 2

William Stanley Jevons published another book, The Principles of Science, in 1874, where the Jevons Number was introduced. Jevons, in this book, wrote, “Can the reader say what two numbers multiplied together will produce the number 8,616,460,799? I think it unlikely that anyone but myself will ever know,” with the included number becoming Jevon’s Number.