Key Points:

- In Jonathan Swift’s 1726 novel Gulliver’s Travels, he inadvertently inserted himself into the history of computers.

- In 1701, Swift anonymously published his first political pamphlet: A Discourse on the Contests and Dissentions in Athens and Rome. From there, he delved into writing more political pamphlets, then relocated to Ireland and continued there.

- Swift’s depictions of a “Frame Engine” in his famous novel became the earliest description of a machine that resembled the modern day computer.

Jonathan Swift, the notable 17th and 18th century Anglo-Irish satirist and author, might not seem like someone who played a part in the creation of the computer. However, in mocking the work of 13th and 14th-century mathemetician Ramon Llull, Jonathan Swift inadvertently made himself a part of the computer’s history with his 1726 novel Gulliver’s Travels. But how did this happen? And where did it fall amongst Swift’s other achievements? Let’s discuss the facts.

Early Life

Jonathan Swift was born in Dublin, Ireland on November 30th, 1667. While he was their second child, he was the only son of Abigail Erick and his namesake, Jonathan Swift. Swift’s father hailed Goodrich, Herefordshire, England. He and his brothers fled to Ireland after the English Civil War brought their Royalist father’s estate to ruin. James Ericke, Swift’s maternal grandfather, was the vicar of Thornton in Leicestershire. In 1634, Ericke was found guilty of Puritan practices. Because of this, Ericke and his family — including Abigail, his young daughter — had to escape to Ireland.

Swift’s father joined his older brother Godwin at his law practice in Ireland. Unfortunately, he died when Abigail was just two months pregnant — a mere seven months before Swift was even born. After being born, Jonathan’s wet nurse took him under her care in her hometown of Whitehaven, Cumberland, England. It was there that he began to develop the skills that would stick with him for a lifetime: Reading and writing. He returned home to his mother in Ireland at the age of three. Not long after, his mother went back to her homeland of England. At this point, Swift was placed in the hands of his uncle Godwin.

When Swift was six, Godwin sent him off to Kilkenny College with one of his cousins. Swift lacked the basic knowledge of Latin expected of Kilkenny College students, and as such, Swift was sent down to a lesser level. Nine years later, at the age of 15, Swift graduated and went off to Trinity College Dublin. Swift’s Trinity College courses were largely about the Middle Ages and the priesthood, most of which was dominated by talk of Aristotelian logic and philosophy. The main takeaway from all this was that it taught Swift how to effectively debate — a key skill in his eventual career as a satirist and author.

Career

Further Schooling

As Swift studied for his master’s degree in 1688, Ireland’s political troubles in the midst of the Glorious Revolution forced him to escape to his mother in England. While there, Abigail secured her son a job as English diplomat Sir William Temple’s secretary and personal assistant. Temple had recused himself from public service at this point in time, residing at his countryside estate, spending his days caring for his gardens, and writing an autobiography. It wasn’t long before Swift took on some of Temple’s former roles in Parliament. Less than three years after meeting, Swift had already met William III and had been sent to London to implore the King to sign off on a bill.

Around this time in 1690, Swift left his position with Temple and returned home to Ireland. He was suffering from bouts of vertigo, and while it was something he’d deal with for the rest of his life, he learned how to manage it and returned to Temple once more. Not long after his return, Swift completed his master’s degree. He departed his job with Temple once again, this time so that he could get ordained and become a priest. He was granted a position within the Church but soon grew to hate it. Once again, Swift returned to Temple’s countryside estate in 1696. He stayed there until Temple’s eventual death in 1699.

Author

Jonathan Swift’s third and final position at Sir William Temple’s estate saw him arranging Temple’s autobiographies and letters and preparing them to be published. Swift was a longtime reader and writer, and it was at this time that Swift wrote his first short satire: The Battle of the Books. It was a humorous response to those who criticized one of Temple’s essays. He angered many of Temple’s close friends and family after the Sir’s death, many of whom did not want to be included in his published memoirs, and as such, Swift was left to hunt for jobs once more after finishing his work with Temple’s manuscripts.

His time filling some of Temple’s roles in Parliament led him to believe he was practically guaranteed a spot of his own, but he was sorely mistaken. Dismayed, he accepted a job as secretary and chaplain to Ireland’s Earl of Berkeley. At this time, around 1701, Swift anonymously published his first political pamphlet: A Discourse on the Contests and Dissentions in Athens and Rome.

Swift continued writing, though not much of it was published at this time. He became increasingly political and prolific, leading to two of the most important publications of his career thus far: A Tale of a Tub and The Battle of the Books in 1704. He continued to involve himself heavily in British politics for the next twenty years or so, acting as a member of the Whig party in politics but presenting much more like a Tory in terms of his religion.

In time, Swift returned to Ireland to turn his skills as a pamphlet writer into a batch of his most notable works: Proposal for Universal Use of Irish Manufacture in 1720, Drapier’s Letters in 1724, and A Modest Proposal in 1729. As he rose through the ranks of Irish politics, Swift worked on what is largely considered his masterpiece: the novel Gulliver’s Travels. It was published in November of 1726 and was an instant smash hit.

What Was Jonathan Swift Known For?

Writing

Today, Jonathan Swift is widely regarded as the most popular Irish author. What’s more, his book Gulliver’s Travels is considered the most popular work of Irish literature the world over. There’s no doubt this is the thing that defines Swift’s legacy. It’s why most of the facts known about Swift’s life revolve around his writing. Without question, Swift is most known for this: his prose, his essays, his tracts, his pamphlets, his periodicals, his poems, his sermons, and his prayers. However, writing isn’t all that Swift did during his lifetime. He also — no matter how inadvertently — played a part in the early history of the computer.

The Frame Engine

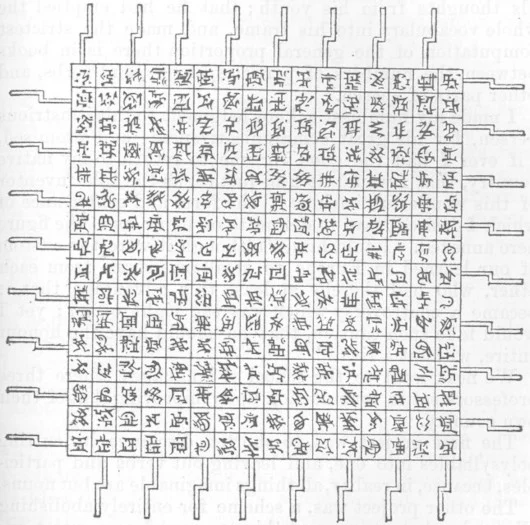

Jonathan Swift’s Frame Engine comes from a passage in Gulliver’s Travels. The novel describes “a frame, which took up the greatest part of both the length and breadth of the room” — “It was twenty feet square, placed in the middle of the room. The superfices were composed of several bits of wood, about the bigness of a die, but some larger than others. They were all linked together by slender wires. These bits of wood were covered, on every square, with paper pasted on them; and on these papers were written all the words of their language, in their several moods, tenses, and declensions; but without any order.”

Swift’s novel describes a professor and his classroom full of students who “took each of them hold of an iron handle, whereof there were forty fixed round the edges of the frame; and giving them a sudden turn, the whole disposition of the words was entirely changed.” While Swift’s novel is clearly mocking the idea, the truth is that this is one of the earliest instances of a writer describing a machine that functions similarly to the computer we know and use today.

Jonathan Swift: Marriage and Personal Life

Marriage

The question of whether or not Swift was married is one that has long perplexed scholars and historians over the years. A woman named Stella (also known as Esther Johnson) played a frequent role in Swift’s writings, leading some to think that Stella and Swift secretly married in 1716. However, the two did not live together and no real evidence exists to back up this idea of a secret marriage. It’s more than likely that Swift and Stella were merely close friends, nothing more.

The same question exists when it comes to Swift’s relationship with Vanessa (also known as Esther Vanhomrigh), another woman who appeared often in his writing. Swift and Vanessa met in London sometime between 1707 and 1709 and she eventually went on to follow him back to Ireland in 1714. Based on the writings between the two, it seems she was the one who loved him while he was more than okay with remaining just friends.

Tragedy

A common theme in much of Swift’s writing is death. He seemed to fear it, based on its frequent appearance in a lot of his major works. In 1738, Swift began to inch closer and closer toward it. He became ill, and by 1742, he began suffering from strokes that left him mute. He feared permanent disability and started to alienate close friends and family, leading many historians to believe Swift had entered a state of full-on insanity at this point in his life — however, it’s possible that it could have merely been dementia he was suffering from. He died October 19th, 1745, and was buried next to Esther Johnson, just as he wished before his passing.

Jonathan Swift: Published Works and Books

- A Tale of a Tub (1704)

- Battle of the Books (1704)

- Predictions for the Ensuing Year (1708)

- “An Argument Against Abolishing Christianity” (1711)

- “Cadenus and Vanessa” (1713)

- Drapier’s Letters (1724)

- Gulliver’s Travels (1726)

- A Modest Proposal (1729)

Jonathan Swift: Quotes

- “Vision is the art of seeing things invisible.”

- “A man should never be ashamed to own that he has been in the wrong, which is but saying, that he is wiser today than yesterday.”

- “Live every day as your last, because one of these days, it will be.”

- “There is nothing constant in this world but inconsistency.”

- “One enemy can do more hurt than ten friends can do good.”