From radio operators to customer service agents, many careers require spellings to be communicated clearly. A misspelled word could lead to a frustrating experience, or it could be a fatal mistake. That’s why the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) uses a standardized spelling method to send signals and spell out words in important communications. Learn more about this phonetic alphabet including its history and uses.

Why NATO Uses Phonetic Alphabet Military Code Words

Describing the position of a rescue helicopter or directing a ship to a particular port requires specific signals. NATO recognized the need for a phonetic alphabet to spell out messages that were easily recognized despite background noise or language barriers.

It took some time for the universal NATO alphabet shortcode to be finalized. It did in 1956, however, and remains a standard communication practice for military branches, civilians, and amateur radio communication.

©Lickomicko/Shutterstock.com

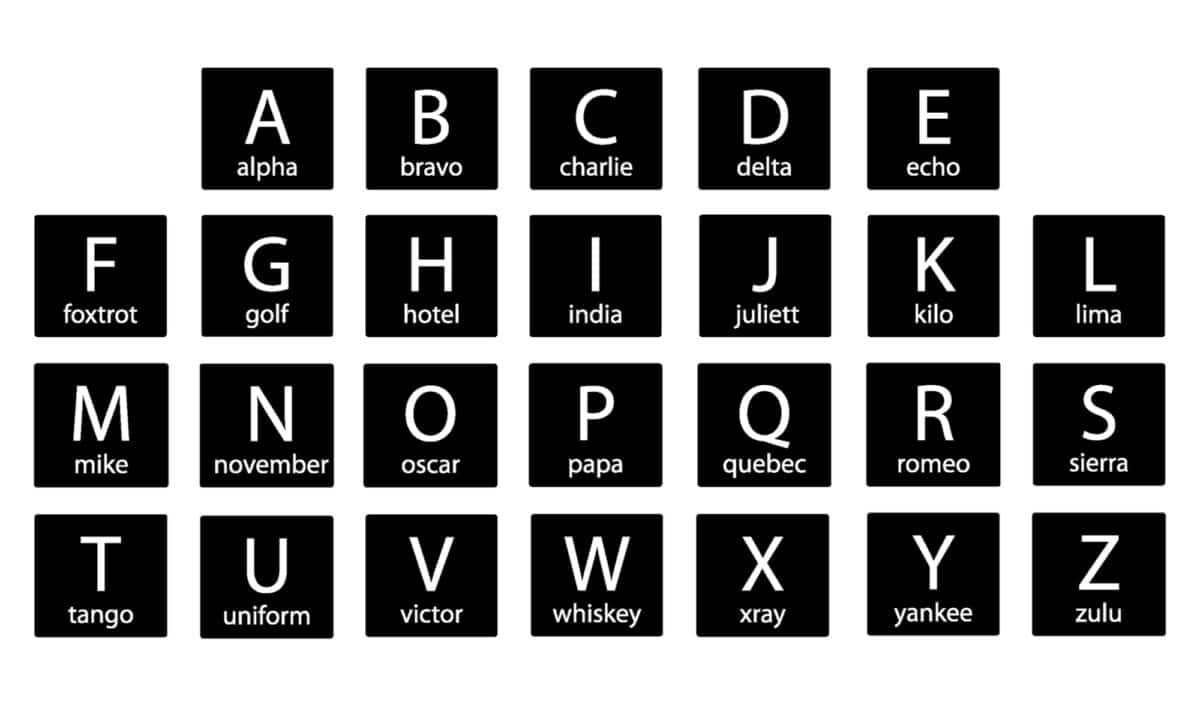

The 26 NATO Alphabet Shortcode Words

There was some debate on the best words to stand for each letter in a recognizable way like using Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, and Delta. Here are the 26 that NATO determined to be part of their phonetic alphabet:

- Alfa (This is the official NATO spelling, though many civilians spell it “Alpha.”)

- Bravo

- Charlie

- Delta

- Echo

- Foxtrot

- Golf

- Hotel

- India

- Juliett

- Kilo

- Lima

- Mike

- November

- Oscar

- Papa

- Quebec

- Romeo

- Sierra

- Tango

- Uniform

- Victor

- Whiskey

- X-ray

- Yankee

- Zulu

History of the NATO Phonetic Alphabet

The NATO alphabet was specifically chosen to ensure every letter not only sounded different than other letters but also was easy to pronounce and understand by all NATO members. The first instance of an internationally recognized phonetic alphabet occurred before the existence of NATO. Explore the different alphabets proposed throughout the years before the 26 official military code words were chosen.

International Telecommunication Union Alphabet

In the 1920s, this alphabet was not only used in the United States but was internationally recognized. The International Telecommunication Union created this alphabet which used the names of global cities and other recognizable names to stand for each letter. Unfortunately, the words weren’t as easy to remember or pronounce. When the U.S. military chose instead to create its own phonetic alphabet, this option was gradually replaced.

Able Baker Alphabet

Both the Army and Navy adopted the Able Baker alphabet, named after the two code words that stand for “A” and “B.” It didn’t include all of the well-known NATO alphabet shortcode words, like Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, and the others. The other branches of the military also adopted it in 1941, with the British Royal Air Force adopting it in 1943.

While popular and used for more than a decade, this alphabet was difficult for other NATO allies to learn. Spanish and French speakers had difficulties with some unusual words and pronunciation choices in military code words. The English composition of Able Baker made its application beyond the U.S. and U.K. military branches limited, so the International Air Transport Association (IATA) developed a phonetic alphabet very similar to the modern NATO alphabet in 1951.

©dennizn/Shutterstock.com

The 1951 IATA phonetic alphabet was reviewed by NATO and altered in a few critical ways. The letters C, M, N, U, and X were all altered and submitted to the International Civil Aviation Organization. On March 1, 1956, the current phonetic alphabet was adopted by NATO and soon became the universal way to clearly communicate in military, civilian, and radio communication.

Other NATO Codes and Signals

The phonetic alphabet is only one standard form of communication adopted by NATO, member governments, and military branches. Here are some other official forms of communication. Some are still commonly used, like ship flag signals. Others, like Morse code, are rarely used.

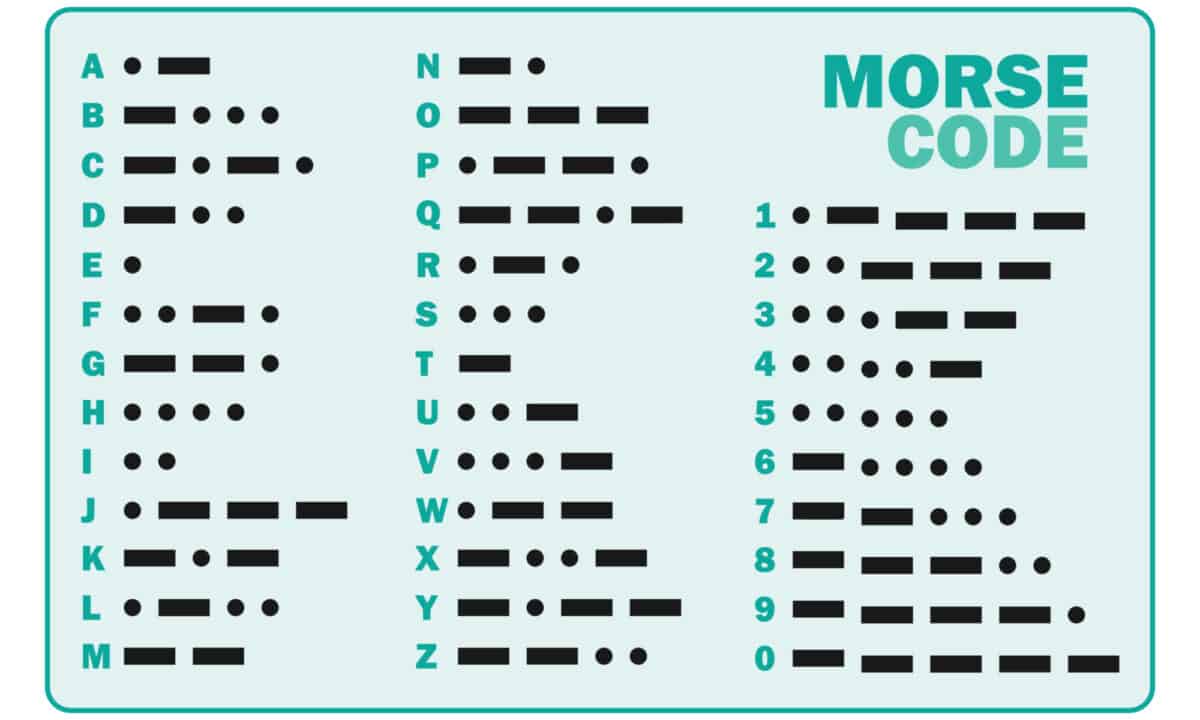

Morse Code

©akilasaki/Shutterstock.com

In the 1890s, Morse code was one of the most popular ways to communicate at a distance. A series of dots and dashes represented letters and could be communicated using lights, clicks, tones, and telegraph signals. It’s been used for civilian communication, international maritime emergencies, and other purposes. Today, it’s only occasionally used for vessels wishing to communicate without using digital transmissions.

Semaphore

Forms of semaphore have been around since at least 1794. This form of communication requires flags to be held in specific positions to communicate numbers or letters. While not as heavily relied on as it was in the past, NATO members still use this to send messages.

Flaghoist Communication

Similar to semaphore, NATO flaghoist communication uses flags as signals. It’s mainly used to communicate between ships. The flags can be combined to create sentences in daylight. It may be more limited for longer messages but can send short messages accurately and quickly.

Panel Signaling

Finally, NATO uses panel signals to send messages to aircraft from ground forces. Ground forces can request medical supplies, emergency support, and other aid from aircraft in the nearby area without using radio communication or other transmissions.