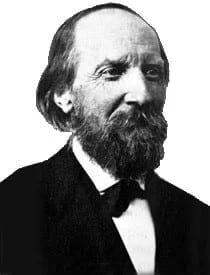

Who was Thomas Hill?

Thomas Hill was an inventor, clergyman, scientist, educator, and university professor. From the halls of Harvard University to the annals of the history of calculating machines, he contributed to scientific, religious, and academic thought in the 19th century. Learn more about his early life, career, and contributions.

Early Life

Thomas Hill was born to Thomas Hill (1771-1828) and his second wife, Henrietta (Barker) Hill (1774-1824) on June 7th, 1818, in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Hill’s father had emigrated to the United States from England in 1791 for religious reasons. In his new country, he began as a farmer, started a business as a tanner, and served as a judge on the court of common pleas.

A lover of nature, Hill’s father taught his children (Thomas had three brothers and five sisters, and he was the youngest) the scientific names of plants and encouraged an interest in the natural sciences. Hill’s mother died in 1824 and his father died in 1828, thus he became an orphan by the time he was 10 years old.

Hill had little formal schooling in his early years, but his mother and sisters taught him to read and cipher. A keen observer with a retentive memory, Hill was a constant and wide reader. He developed an early interest in botany, science, philosophy, and mathematics. By the time he was twelve years old, Hill had read the works of Benjamin Franklin and Erasmus Darwin.

Hill served as an apprentice in a newspaper office from 1830 to 1833. In 1834 he studied under his eldest brother at Lower Dublin Academy in Holmesburg, Pennsylvania.

Although he was interested in civil engineering, Hill became an apprentice to an apothecary in his home place, serving in this capacity until 1838. Hill entered Harvard University in 1838 and received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1843.

Career

After initial apprenticeships and studies, Hill went on to a thriving and diverse career. His career consisted mainly of serving as a minister and as a university president. He was also a mathematician who wrote about mathematics and created an important key-driven calculating machine invention. Near the end of his life, however, Hill traveled and held several positions before his death in 1891.

Hill the Minister

In 1845, Hill received his divinity degree from the Harvard Divinity School and entered the ministry for 14 years. Hill served at the First Church of Waltham, Massachusetts from 1845 to 1859.

It was during this time that Hill established his reputation, not only as a man of God but also as a scientist, educator, and writer. A popular speaker, he gave the Phi Beta Kappa oration at Harvard University in 1858 and presented a series of Lowell Institute lectures on the Mutual Relation of the Sciences in 1859.

During his final years in Waltham, Hill served on the Waltham School Committee. He was constantly encouraging and promoting new ideas and methods of instruction, including the introduction of phonetic spelling in public schools.

Hill the University President

In 1859, Hill accepted the presidency of Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Hill’s appointment was ill-timed, however, as the American Civil War forced the college to close in 1862. That same year Cornelius Conway Felton, the President of Harvard University, died suddenly, and Hill was asked to succeed him.

Returning to Harvard University, Hill had high hopes for the future and brought about several changes. Under his administration, the undergraduate curriculum adopted an elective system, permitting student choice in selecting courses. The standards for admission were raised, an Academic Council made up of the faculties of the college and professional schools was established, scholarships for the support of graduate students were endowed, a program of University Lecturers was introduced, and new chairs for professorships in geology and mining were founded.

Despite these apparent successes, Hill’s years at Harvard were not happy. He had difficulty in his dealings with faculty and in governing the University. Hill’s experience with his physical problems at this time also contributed to his unhappiness. Tired and overwhelmed both personally and professionally, Hill resigned from his office in 1868.

Hill the Traveler

In 1869, Hill spent a year resting and traveling. He was elected to the Massachusetts state legislature from Waltham and served for one year in 1871. In 1872, Hill sailed with his friend Louis Agassiz on an expedition to South America. Returning to the ministry in 1873, Hill accepted a position at the First Church in Portland, Maine.

For the next 18 years, Hill was happy spending his time preaching, writing, lecturing, and pursuing his scientific and educational experiments as a scientist. In 1891, Hill became ill, suffered for several months, and died in Waltham, Massachusetts.

What Did Thomas Hill Invent?

While never his full-time career, Hill is remembered for his important contributions to calculating machines. He had two significant inventions: an instrument for calculating eclipses and patented the key-driven calculating machine.

Instrument for Calculating Eclipses

In college, Hill distinguished himself in mathematics. He invented an instrument for calculating eclipses and occultation while still a student. He doesn’t appear to have patented or improved upon the invention during his lifetime.

Hill Calculating Machine

Hill obtained a patent for an improved arithmometer In 1857. The arithmometer used 10 digits and was an important addition to 19th-century arithmometer designs, but didn’t create a product as a result of the patent.

Thomas Hill: Marriage, Divorce, Children, and Personal Life

Marriage

On November 27th, 1845, in Waltham, Cheshire, Thomas Hill married Anne Foster Bellows (1817-1864). He remained with his first wife until she died in 1864 in her 40s.

Two years later, Hill married Lucy Elizabeth Shepard (1837-1869) on July 23rd, 1866. Lucy tragically died after just a few years, in 1869.

Children

Hill and Anne Foster Bellows had six children—Mary Bellows (1846-1911), Henry Barker (1849-1903), Katherine (1851-1926), Elizabeth Joy (1854), Anne Bellows (1857), and Thomas Roby (1864-1923). He had one son with his second wife, Otis Shepard Hill in 1868.

Tragedy

Thomas Hill outlived both of his wives, losing both Anne in 1864 and Lucy in 1869. In addition to this, his youngest son, Otis Shepard Hill, suffered from an incurable illness.

Thomas Hill: Awards and Achievements

In addition to his distinguished service at Harvard University, Antioch College, and First Church of Waltham, Massachusetts, Hill received an award for his first invention during his college years.

Scott Medal, Franklin Institute

Hill’s invention of an instrument for calculating eclipses and occultations, for which he was awarded the Scott Medal from the Franklin Institute.

Thomas Hill Published Works and Books

Christmas, and Poems on Slavery, 1843

Hill wrote and published a small collection of poems while still a college student. It was dedicated to Eliza Lee Follen, who was active in the anti-slavery movement.

Geometry and Faith, 1849

This not only described his views on geometry, but also his religious doctrine and how it applied to mathematics.

First Lessons in Geometry, 1855

In 1855, Hill published a mathematical textbook focused on geometry.

Second Book of Geometry, 1862

This book was his second mathematical textbook, first published in 1862.

Jesus, the Interpreter of Nature, and Other Sermons, 1859

This compilation of sermons highlights Hill’s religious doctrine and convictions from his time as a minister.

Practical Arithmetic, 1881

This book was another mathematical textbook, written after his time as president of Harvard University.

Thomas Hill Quotes

As an avid writer, speaker, and lecturer, several quotes remain of Thomas Hill. Here are a few of the most popular:

- “The discoveries of Newton have done more for England and for the race, than has been done by whole dynasties of British monarchs; and we doubt not that in the great mathematical birth of 1853, the Quaternions of Hamilton, there is as much real promise of benefit to mankind as in any event of Victoria’s reign.”

- “Mathematics and Poetry are … the utterance of the same power of imagination, only that in the one case it is addressed to the head, and in the other, to the heart.”

- “…the labors of the mathematician have outlasted those of the statesman, and wrought mightier changes in the condition of the world. Not that we would rank the geometer above the patriot, but we claim that he is worthy of equal honor.”