Who was Samuel Morland?

Samuel Morland was an English academic, inventor, mathematician, diplomat, and spy. He lived in the 17th century and was also proficient in several languages, including French, Greek, and Hebrew. Besides inventing three calculating machines, he also created a variety of other devices. He is credited with early developments in the fields of steam power, hydraulics, computing, and for inventing what was the first mechanical calculator. He is also credited with what would have been the first megaphone. The following are some of the general highlights of his life.

- 1661– A Royal Warrant was issued for a grant to Morland for the sole use, during fourteen years, for his invention for raising water out of pits with the force of air and powder conjointly.

- 1662– He invented a calculating device for multiplication and division.

- 1663– Morland invented a calculating device for Trigonometry.

- 1666– Morland obtained a patent for making metal fire-hearths. This same year, he devised an arithmetical machine that had the four fundamental rules of arithmetic.

- 1671– In his treatise Tuba Stentoro-Phonica: An Instrument of excellent use, as well at Sea, as at Land, he invented the speaking trumpet, an early form of a megaphone.

- 1675– Morland received a patent for a plunger pump that was able to raise great quantities of water that completed the job with far less strength needed than that of either a chain or another pump.

- 1681– Morland was appointed the magister mechanicorum, which means the master of mechanics, for work on Windsor’s water system.

Early life

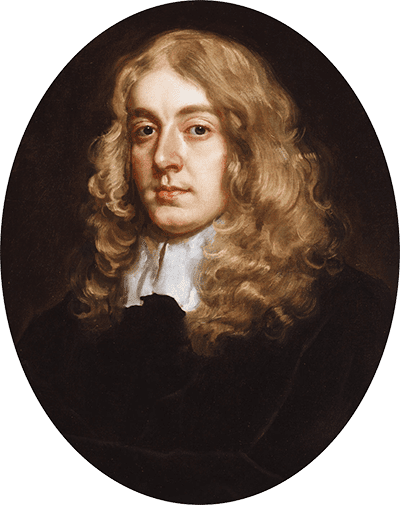

Samuel Morland was born in 1625 at Sulhamstead Bannister, Berkshire, England. He was the son of Thomas Morland. The elder Morland was a rector in Berkshire, in Sulhamstead Bannister. Samuel Morland was educated at Winchester College in Hampshire starting in 1638. He entered as a sizar at Magdalene College in Cambridge in 1644 and graduated in 1649. Morland studied Mathematics, Latin, and several other languages.

After leaving college, Morland entered public service and worked as both a diplomat and a spy. In 1653, Morland was included in an embassy to the Queen of Sweden as part of a military alliance. The Queen was a patron of the sciences, and it was likely in her court that Morland became acquainted with the Pascaline, a calculating device invented by Blaise Pascal. This likely led to Morland constructing his three calculating devices approximately 10 years later.

In 1655 Oliver Cromwell sent Morland on a trip to Italy to protest the brutality taken against the Waldensians, a protestant group that had separated from the Catholic Church.

©Peter Lely, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – Original / License

Career

Phase 1

Samuel Morland started out working as a diplomat and a spy. He eventually became part of a clandestine group known at the time as the “Sealed Knot.” The Sealed Knot was a group of only six men who came together in 1653 to help the royalist side in England. Leading a double life as a spy began to take a toll on Morland and he reportedly stated that he often feared before going to bed that he’d be taken out before morning with his flesh torn from his bones with hot pincers.

Phase 2

In the 1660’s Morland began turning his time and energy toward inventing various machines based on his knowledge of hydraulics and his skill as a mathematician. He invented three separate calculating devices. Morland’s inventions became quite popular and London instrument makers were still selling Morland’s devices as late as 1710. He also worked on projects that improved the water supply to Windsor Castle. In 1675 he received a patent for a plunger pump that was able to bring in larger amounts of water than what was currently brought forth using a chain or other types of pump methods.

He even performed experiments with gunpowder, creating a vacuum to suck in water. Morland invented pumps that could be used for industrial, marine, and domestic uses. His work is often thought of as inspirational for the later development of the steam engine.

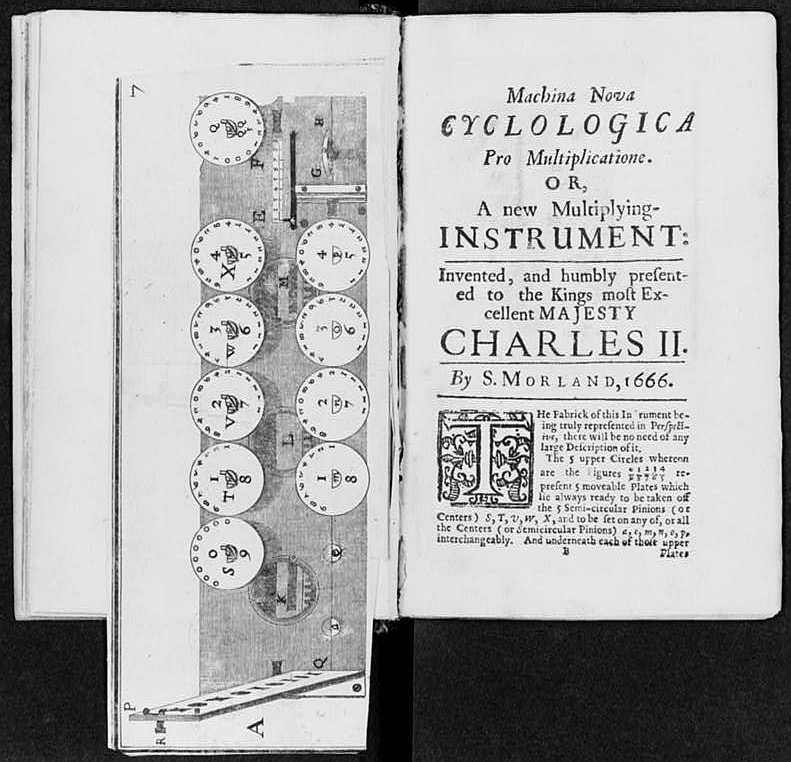

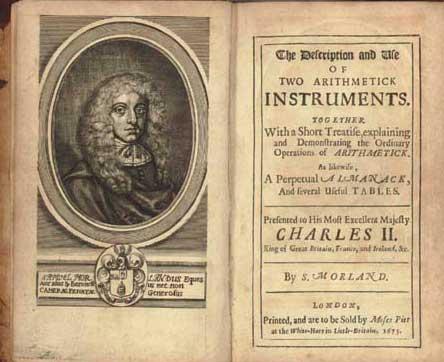

©Samuel Morland (inventor). Engraver unknown., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons – Original / License

What Did Samuel Morland Invent?

The arithmetical machines of Samuel Morland were devised between 1662 and 1666 and were presented to King Charles II as well as a general audience.

Invention 1

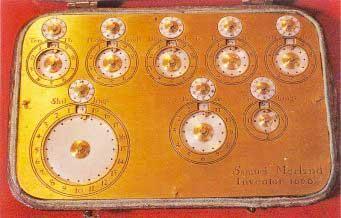

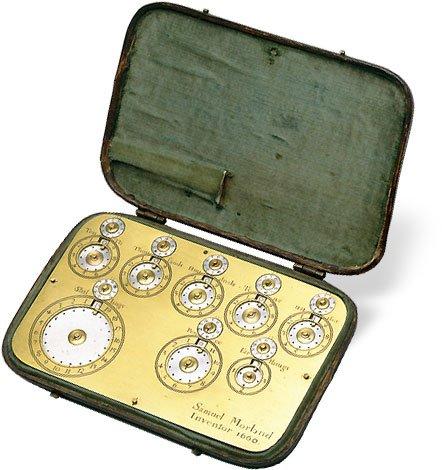

Using his skills in computing and as a mathematician, Morland’s first machine was a simple adding device, similar to Ciclograf of the Italian Tito Livio Burattini, produced in the late 1650s. Made of silver and brass, the device presented what was the first pocket calculator of its time. It measured only 4 by 3 inches and was less than a quarter of an inch thick (122 x 71 x 8 mm).

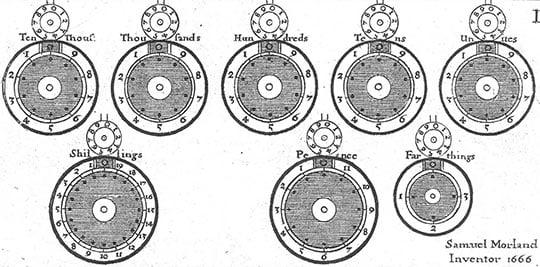

On the lid of the device were mounted eight pairs of graduated dials. The scales of the dials were inscribed on the ring around them. The lower three scales were divided into 4, 12, and 20 parts and were inscribed and used for calculations in the English currency units of the 17th century—guinea (which was equal to 20 shillings), shilling (which was equal to 12 pennies), and penny (which was equal to 4 farthings). The upper five big dials had decimal scales and were inscribed with words unit, tens, hundreds, thousands, tenth.

Across the periphery of each big dial were made openings, according to the scale of the dial—4, 10, 12, or 20. In these openings could be put a stylus, and the dial could be rotated. During this rotation, in a little window in the upper part of each scale could be seen the appropriate number. Below each window was mounted a stop-pin, which was used for limiting the rotation during adding operations. Over each big dial was mounted a smaller one, which served as a counter of the revolutions of the big dial. One-toothed gearing was used for that purpose. The lower dial had one tooth while the upper dial had ten teeth. This made a full revolution of the lower dial with a result of 1/10 revolution of the upper one.

The adding operation was performed by rotating the appropriate dials in the clockwise direction, pushing the stylus into the opening against the appropriate number, and turning the dial until the stylus would be stopped by the stop-pin. The subtraction could be done by rotating dials in the counter-clockwise direction, pushing the stylus in the opening below the window, and rotating the dial until it moved below the appropriate number.

The machine, however, didn’t have a tens carry mechanism, and this made it useless for practical needs. In 1668 Morland published a short description in a London newspaper, trying to market it, but without success.

Invention 2

The second calculating machine Morland invented was based on the principle of Napier’s bones. This device was described in the book by Morland under the name Cyclologia.

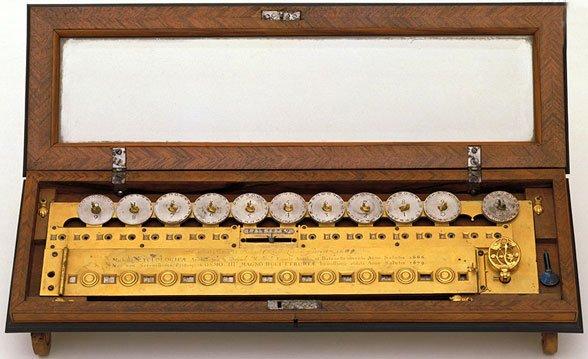

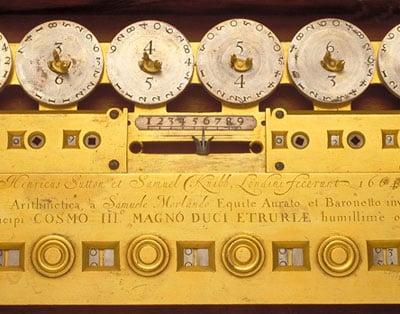

Morland ordered the manufacturing of the device by the famous English mechanicians Henri Sutton and Samuel Knibb. This particular machine was donated by Morland to Grand Duke Cosimo III de’ Medici in 1679. The dedication to the Grand Duke contained an obvious error: it gives 1666 as the year of invention and 1664 as the year of manufacturing.

The device was elaborated by silver, gilt, and silvered brass, wood, and crystal. The dimensions were 18 x 55.5 cm. Actually, the multiplication machine of Morland simplified only the intermediate products, using the principle of Napier’s rods. There was no automatic or mechanical carry mechanism provided.

The digits from the ten Napier’s rods were inscribed across the periphery of 10 thin metal disks in such a manner that the units and tens of the rods were placed on the opposite ends of the circle. There were two rows of axis in the device, the upper axis was fixed, while the lower could be rotated.

In the row of windows, placed between the two axes could be set numbers. Therefore, it served as a mechanical memory. To perform a multiplication, the appropriate disk must be removed from the upper fixed axis and mounted to the lower working axis. Each of the lower axes was attached to a small pinion in the body of the machine, and this pinion was engaged with a toothed strip. This strip could be moved in a horizontal direction using the key, which could be seen in the lower right part of the lower figure, and its movement was marked by an arrow, which could be moved across a scale.

When the appropriate disks were set (according to the digits of the multiplicand), the lower part of the machine was covered by a lid, which had windows. The key had to be rotated by the operator until the arrow came to the digit of the multiplier on the scale. During this rotation, the toothed strip could move and rotate the pinions that were engaged with it. Thus, in the lower row of windows could be seen the product. If the factors were multi-digital, then this action must be repeated until all digits would be used.

For example, to multiply 23 by 7, the user would first take the discs for 2 and 3, place them on the central posts and close the door so that in the window the number 23 appears (3 in the left-most window and 2 in the left side of the second pair of windows). Then the user would turn the key until the pin on the slider scale pointed to 7. Each time the key was turned the discs were rotated once, which advances the display of the multiplication table for the selected numbers (2 and 3) by one.

The windows were constructed so that a number on the leftmost edge of one disc appeared next to the number on the rightmost edge of the next disc. The final answer had to be obtained by adding the adjacent numbers in the windows, either with pen and paper or, as the inventor suggested, with the help of his instrument for addition. To finish the example, after discs 2 and 3 had been rotated 7 times, the numbers in the display window would read: 1 4 2 1. The final result was found by adding the adjacent digits to give 161.

Invention 3

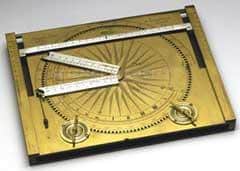

Besides the two above-mentioned calculating devices, in 1663, Morland invented a third one. It was a device that could be used for trigonometric calculations (see the nearby photo). He called this the Maccina Cyclologica Trigonometrica. The trigonometer allowed the operator to perform trigonometry by drawing out a problem and measuring the solution as with drawing instruments but without the need for pen and paper. It was a set of three rulers set into a divided circle that could be moved about using dials to form a triangle of any shape.

On April 16, 1668, Morland printed short descriptions of the two adding devices in the London Gazette. Despite the excellent workmanship of the arithmetic devices of Morland, they were not very useful for practical needs, moreover, some of his contemporaries were not so fascinated by their usefulness.

In fact, the famous scientist, Robert Hooke, wrote in his diary on January 31, 1673: “Saw Sir S. Morland’s Arithmetic engine Very Silly.” The machines of Morland were, however, appreciated by King Charles II and Cosimo III de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, which was more important for Morland as a typical courtier–inventor.

Samuel Morland: Marriage, Divorce, Children, and Personal Life

Net Worth

It is not known exactly what Samuel Morland’s net worth was. Despite his many accomplishments and connections to royalty in England, he did struggle financially throughout his life.

Marriage

Samuel Morland was married four times.

- In 1657 he married Susanne de Milleville in Normandy. She died in 1668.

- In 1670 he married Carola Harsnett in Westminster Abbey. She died in 1674.

- In 1676 he married Anne Fielding in Westminster Abbey. She died in 1680.

- In 1687 he married Mary Ayliffe at the Knightsbridge Chapel in Middlesex. They were divorced in July 1688.

Divorce

Morland obtained a divorce from Mary Ayliffe on July 16, 1688.

Children

Samuel Morland had five children. He had three from his first wife and two with his second.

Tragedies

Morland endured several difficulties and tragedies throughout his life. This included financial problems as he was always short of cash. Morland spent quite a bit of money on his machines and experiments.

He was married four times, with three of his wives dying young. The last wife he divorced in 1688. He had five children, but right before his death, he disinherited his only son. Also, near the end of his life, he began to go blind and completely lost his sight around 1692.

Samuel Morland: Awards and Achievements

Samuel Morland was knighted by the King. He became a baronet of Sulhamstead Banister on May 20, 1660. He also received the honor of being a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber and Clerk of the Signet.

Samuel Morland Published Works and Books

Book 1

Samuel Morland wrote the book, The description and use of two arithmetick instruments. The book was published in London in 1673. This is the first book on a calculator, written in English, and the first separate work on the subject after Napier’s Rabdologiae. There was little else in English on calculating instruments for more than 160 years from this book to the publication of Babbage in 1827.

The book may also be considered the first comprehensive book in computer literature, as Blaise Pascal published nothing about his own machine, except an 18-page pamphlet in 1644.

Book 2

History of the Evangelical Churches of the Valleys of Piedmont was a book written by Morland regarding the 1655 massacre in La Torre. The book was published in London in 1658.

Book 3

Morland wrote an autobiography in 1661.

Samuel Morland Quotes

Samuel Morland was quoted in his autobiography, “….finding myself disappointed of all preferment and any real estate, I betook myself to the Mathematics and Experiments such as I found pleased the King’s Fancy.“

He wrote this regarding the fact that even though he had been granted titles, and even a pension by the King, he still was not considered wealthy and likely struggled financially throughout his life.