Key Points:

- Jacques de Vaucanson was a French and inventor responsible for designing the world’s first robots.

- Vaucanson developed his first mechanical devices based on his understanding of anatomy. They mimicked biological functions like circulation, respiration, and digestion.

- In 1737, he built three mechanical automatons: The Flute Player, a life-size figure of a shepherd that played the tabor and the pipe; The Tambourine Player; The Digesting Duck, Jaques’ most popular invention.

Who was Jacques de Vaucanson?

Jacques de Vaucanson (1709–1782) is a French engineer and inventor. He is responsible for creating the world’s first robots, the first automated loom, and building the first all-metal lathe.

Early life

Jacques Vaucanson was born in the French town of Grenoble in 1709. Vaucanson grew up poor and was the tenth child of a glove-maker. As a little boy, Jacques quickly revealed his talent with mechanics by fixing watches and mechanical devices driven by clockwork. He aspired to become a clockmaker.

In 1715 Jacques’ family sent him to study at the Jesuit school in Grenoble (now Lycée Stendhal). Then in 1725 Vaucanson joined the Les Ordre des Minimes in Lyon. Initially, Jacques intended to follow a course in religious studies. However, when he met the surgeon Claude-Nicolas Le Cat and learned the details of anatomy, he regained his interest in mechanical devices.

His understanding of anatomy allowed him to develop his first mechanical devices, which mimicked biological functions like circulation, respiration, and digestion.

Career

In 1728 Vaucanson decided to leave the monastery to devote himself to his mechanical interests, and departed to Paris, where he remained until 1731. In Paris he studied medicine and anatomy at the Jardin du Roi, being encouraged and supported by the Parisian financier Samuel Bernard, one of the wealthiest men of his time.

In 1731 Vaucanson left Paris for Rouen, where he met the famous surgeon and anatomist Claude-Nicolas Le Cat (1700-1768), whose own interest in replicating human anatomical forms and movements. Like clockwork this inspired Vaucanson to begin work on his first automaton.

Later Vaucanson met another famous French surgeon and economist, François Quesnay (1694-1774), who also encouraged him to create artificial creatures to put in evidence most of human or animal biological functions. Thus the young Vaucanson decided to further develop knowledge in anatomy by making living anatomies

In 1732 Vaucanson traveled around France exhibiting his first automaton which he described as “a self-moving physical machine containing many automata, which imitate the natural functions of several animals by the action of fire, air, and water.”

In 1737, he built The Flute Player. The Flute Player was a life-size figure of a shepherd that played the tabor and the pipe. That same year, Vaucanson created two more mechanical devices – The Tambourine Player and The Digesting Duck. The Digesting Duck is Jaques’ most popular invention. It was a mechanical duck that had over 400 moving parts in each wing. It could flap its wings, drink water, pretend to digest grain, and pretend to defecate. Due to The Digesting Duck, Vaucanson is credited for inventing the world’s first flexible rubber tube which acted as the duck’s intestines.

In 1741 he was appointed as the inspector of the manufacture of silk in France by Cardinal Fleury. Here he was in charge of undertaking reforms of the silk manufacturing process. During this time, Vaucanson promoted changes for automating the weaving process. Four years later, he created the first completely automated loom.

Vaucanson became a member of the Académie des Sciences in 1746.

In 1760, he invented the first industrial metal cutting slide rest lathe – it was designed to produce rollers for putting patterns into silk cloth. These were made out of copper rather than steel.

What Did Jacques de Vaucanson Invent?

The Flute Player

In 1733 Jacques de Vaucanson signed a contract with Jean Colvée, a man of the cloth whose interests included chemistry, natural history, geography, and various business ventures, to build and exhibit another automation. Three years later, Jacques spent Colvée’s funds and signed into an agreement with a Parisian gentleman, Jean Marguin, to build an automated flute player in exchange for financial support. Marguin would retain one-third ownership of the completed automaton and receive half the money taken in when exhibited.

In 1737 Vaucanson completed The Flute Player. The Flute Player was a life-size figure of a shepherd. It played the transverse flute and had a repertoire of twelve songs. The tunes were played on a real instrument.

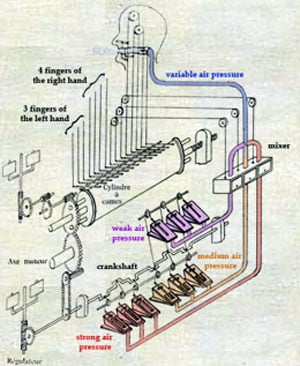

The fingers were carved in wood with a piece of leather at the point where they cover the holes. The entire figure is made of wood except for the arms which are made of cardboard.

The Flute Player was seated on a rock put on a pedestal, like a statue. The case, enclosing a large part of the weight engine mechanism, housed a wooden cylinder (56 cm in diameter and 83 cm in length), which turned on its axis. The Flute Player was covered with tiny protrusions. It sent a pulse to fifteen levers that controlled the output of the air supply – this controlled the movements of the lips, the tongue, and the articulation of the fingers. This allowed the figure to play its tunes on a real instrument.

In 1738, he demonstrated The Flute Player before the French Academie. Later, he opened an exhibition to the public first at the fair of Saint-Germain, then in the reception room of the Hôtel de Longueville in Paris, where he initially presented The Flute Player, but at the end of the year added two other automata.

When Vaucanson presented The Flute Player to the French Academy of Science, he also wrote a lengthy report—a dissertation entitled “Mechanism of the automaton flute player” (“Mécanisme du flûteur automate”). His dissertation carefully described how his automaton could play exactly like an alive person.

Jacques de Vaucanson’s dissertation had all the clarity and precision of what this machine is capable of. It proves both Vaucanson’s intelligence and his extensive knowledge of all the mechanical parts.

The Tambourine Player

1738 was a busy year for Vaucanson. In addition to The Flute Player, he created two other automata – The Tambourine Player and The Digesting Duck (Canard Digérateur), which is considered his masterpiece.

Very little information has been published about The Tambourine Player, but the automation is well regarded, similar to The Flute Player. The Tambourine Player was a life-sized man dressed like a Provençal shepherd, who could play 20 different tunes on the flute of Provence (also called galoubet) with one hand, and on the other would play the tambourine with all the precision and perfection of a skillful musician. It must have been equipped with a very complex mechanism because it could play two different musical instruments.

According to Vaucanson, the galoubet was the “most unrewarding and inexact instrument that exists.” He also made the following note: “A curious discovery about the building of this automaton is that the galoubet is one of the most tiring instruments for the chest because muscles must sometimes make an effort equivalent to 56 pounds…”

The Digesting Duck

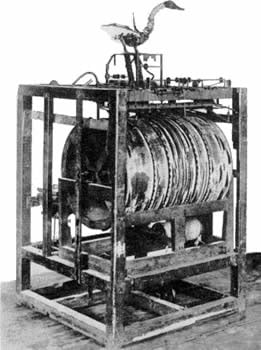

The next automata he created was The Digesting Duck (Canard Digérateur). The Digesting Duck was also referred to as the mechanical duck or the clockwork duck. It is considered his masterpiece. The Digesting Duck was made of gilded copper and had over 400 moving parts. It could quack, flap its wings, drink water, digest grain, and defecate like a living duck. Vaucanson’s duck supposedly demonstrated digestion accurately. His duck contained a hidden compartment of “digested food,” so what the duck defecated was not the same as what it ate.

The goal with the automata was to entertain the wealthy and powerful to gain their funding. With his work on The Digesting Duck – Vaucanson is credited with having invented the world’s first flexible rubber tube with the process he used to build the duck’s intestines.

Due to the open structure of its abdomen, the audience could follow the digestive process from the throat to the sphincter, which ejected a sort of green gruel.

Mechanical creatures, like the mechanical duck, were a fad in Europe and could be classified as toys. They were recognized as being revolutionary in their mechanical life-like sophistication.

All three of Vaucanson’s automatons had great success, and in 1743 he sold them to some entrepreneurs from Lyon, who toured with them for nearly a decade, showing them throughout Europe. Admission charged at these exhibitions and the automata appear to have brought in considerable revenue. The musical automatons were lost or destroyed at the beginning of the 19th century, and the duck burnt in a museum in Krakow, Poland in 1889. They did not survive to the present time.

The First Completely Automated Loom

In 1741 Vaucanson was charged with undertaking reforms of the silk manufacturing process because, at the time, the French weaving industry had fallen behind England. He was appointed by Cardinal André-Hercule de Fleury, chief minister of Louis XV. He inspected the manufacturing of silk in France. In 1742 Vaucanson promoted wide-ranging changes for automation of the weaving process. Three years later, he created the world’s first completely automated loom. Vaucanson drew from the work of Basile Bouchon and Jean Falcon. Unfortunately, Vaucanson’s loom was not successful. His proposals were not well received by weavers, and they pelted him with stones in the street and eventually led to strikes and social unrest in Lyon.

The hooks of the loom that lifted the warp threads were selected by long pins or needles, which were pressed against a sheet of punched paper that was draped around a perforated cylinder. Each hook passed at a right angle through an eyelet of a needle. When the cylinder was pressed against the array of needles, some of the needles pressing against solid paper would move forward. This would tilt the corresponding hooks.

The hooks that were tilted would not be raised, so the warp threads that were snagged by those hooks would remain in place. The hooks that were not tilted, would be raised, and the warp threads that were snagged by those hooks would also be raised. By placing his mechanism above the loom, Vaucanson eliminated the complicated system of weights and cords (tail cords, simple pulley box, etc.) that had been used to select which warp threads were to be raised during weaving. Vaucanson also added a ratchet mechanism to advance the punched paper each time the cylinder was pushed against the row of hooks.

Although the idea behind the loom was good and the prototypes worked well – the issue that Vaucanson had was that the metal cylinders were expensive and difficult to produce. The cylinders could only be used to make repetitive designs unless you switched to new cylinders. This proved to be too time-consuming and laborious.

Vaucanson’s technology was refined by Joseph-Marie Jacquard more than a half-century later, and it revolutionized weaving. In the 20th century, this technology would be used to input data into computers and store it in binary form.

Afterward, Vaucanson went back to automation and began a project to construct an automaton figure that simulated movements of the animal functions (Ex. the circulation of the blood, respiration, digestion, the operation of muscles, tendons, nerves, etc.) However, this was too ambitious a project, and in 1762, he began to work on the more modest project of a machine. He wanted to create a machine that would simulate just the circulation of the blood, using rubber tubes for veins. But this project, too, remained unfinished because of inadequacies in contemporary rubber technology.

Jacques de Vaucanson: Marriage, Divorce, Children, and Personal Life

Net Worth

Unknown. Estimated to be in the millions.

Marriage

Jacques de Vaucanson married Magdeleine Rey in 1753

Children

Jacques de Vaucanson and his wife, Magdeleine Rey, had one daughter, Angélique-Victoire. Rey died after birth.

Tragedy

Vaucanson died on November 21, 1782 at 72 years old.