Humans are innovators. We’re always looking for a smarter, faster, more efficient way to do things. And if we can build a device to do it for us, so much the better.

One of the things that we’ve tried to automate was performing basic math calculations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division). The first calculator, the abacus (also known as the Suanpan), dates back to at least 1200 C.E. This device featured beads that the user would slide manually on wires that were mounted in a frame.

Blaise Pascal invented the first mechanical calculator, which could only be used for addition and subtraction, in 1642. A myriad of inventors created calculators between then and 1880, when Arthur Ewing Shattuck invented the Centigraph Adding Machine. Let’s find out more about this device.

Centigraph Adding Machine: History

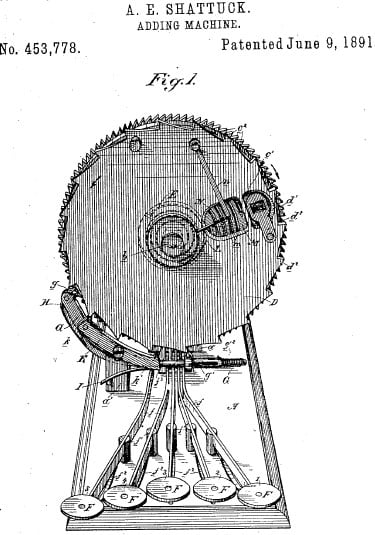

Arthur Ewing Shattuck invented the Centigraph Adding Machine in 1880, at which time he first filed for the patent. Arthur E. Shattuck of San Francisco, California, got four calculating devices patents in the United States and one in Canada. The third (No363972 from 1887, co-authored by Brainard Smith) and fourth (No453778 from June 9, 1891) patents were for a simple five-key single-column adder (similar to the earlier adders of Marshall Cram and Lawrence Swem), the second version of which was manufactured and sold in small quantities in the 1890s by the company American Adding Machine Co., Atlanta, under the name Centigraph Adding Machine.

The Centigraph Adding Machine is an adding machine that has been around since 1880. Incredibly, Arthur acquired the patent (no. 453,778) 11 years later of its invention. The Centigraph Company had already been established by that time, in the preceding year of 1890. The firm used to be situated at 34 Maiden Lane in New York City, which was previously the location of toy importers Purdy and Robbins. Until 1893, significant reviews and ads for the Centigraph began to appear in various magazines.

Centigraph Adding Machine was one of the first typewriters mentioned in history, alongside Williams typewriters. The Centigraph Adding Machine was supplied and demonstrated with numerous Williams items by and outfit from Plymouth, England, according to an October 14, 1893 issue of The Phonetic Journal, a U.K. journal.

It’s impossible to discover proof that The Centigraph Company sold or even manufactured the adding machine after 1893. The rights to manufacture Centigraph Adding Machines were sold to the American Adding Machine Company (AAMC) of Atlanta, Georgia, probably around 1902. It happened when The Cotton States & Belting Supply Company (also based in Atlanta) expressed interest in purchasing the AAMC, primarily for the Centigraph business. Because commercials for the Centigraph began appearing again in 1903, but this time with the AAMC’s name on them, the transaction never took place.

Centigraph Adding Machine: How It Worked

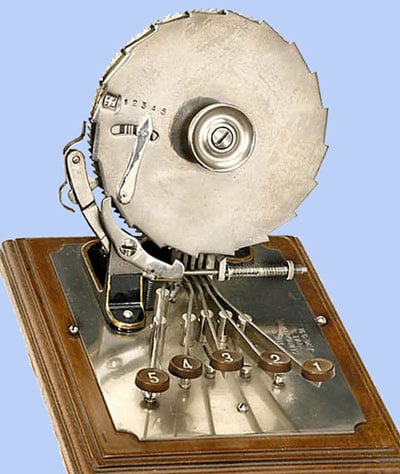

The Centigraph Adding machine has five keys. The plate is twisted to the point where the ciphers may be viewed via its aperture by pressing the keys. For digits higher than five, a user must press two keys simultaneously. For instance, to input the number seven, one has to press five and two together. Prompting these numbers caused the plate to shift to the right, five numbers to the left, and figure 7 appeared in the aperture. The scale can count up to 99, but there is a five-positional pointer for hundreds, allowing the total to reach 599.

The keys 1, 2, 3, and 4 control pawls on a disc with 100 notches around its circle, while the 5 key controls a pawl on a disc with 20 apertures around its circumference. In opposing directions, the two discs spin. The discs are all fixed on the same axis and are only linked by a coiled spring that wraps around that axis. The digits 1-99 are printed on the 100-notch disc, and the total is displayed via a square hole in the 20-notch disc. The 100-notch disc has a spiral groove through which a pin carried at the end of a pointer pivoted to the 20-notch disc traverses. This pointer shows the hundreds up to 500.

Centigraph Adding Machine: Historical Significance

An adding machine is a type of mechanical calculator that is typically used to do accounting computations. The first adding machines in the United States were generally constructed to read in dollars and cents. Centigraph was standard office equipment until the 1970s when they were phased out in favor of calculators, and then personal computers began to replace them about 1985.

Arthur E. Shattuck of San Francisco, California, was a holder of four USA and one Canadian patents for calculating devices. The first (№268135 from 1882) and second (№349459 from 1886) patents (received along with Charles Thorn) are for chain adders, which never reached the market. The third (№363972 from 1887, along with Brainard Smith) and fourth (№453778 on June 9th, 1891) patents however, were for a simple 5-key single-column adder (similar to the earlier adders of Marshall Cram and Lawrence Swem), the second version of which will be manufactured and sold in small quantities in 1890s under the name Centigraph Adding Machine (also Centigraphe and Centagraph) by the company American Adding Machine Co., Atlanta.